Affect is Protocol

When you have hammers for hands everything looks like a fingernail.

Picture yourself sitting in a darkened movie theater, as the first trailer begins to play. It’s a historical drama about naval warfare during the Napoleonic era. What do you see?

What kind of question is that? It’s your hypothetical! I see some boats, the ocean, movie stars, you know, typical movie trailer stuff.

Yeah, that’s how it works for me, too. But now, imagine that you’re a historian who is an expert on the tactics of 19th century ship combat. Imagine how your eyes would light up when this trailer started, imagine what details you would notice.

Now imagine that you are a special effects programmer who specializes in fluid dynamics and water simulation.

Now imagine that you are a costume designer, or a vocal coach, or an optical engineer who designs movie projectors, or someone who edits film trailers for a living.

In each case, you would see the same thing, in terms of raw sensory input. But what you saw would be totally different, in terms of the information you were receiving. You would see things that are invisible to me, because I don’t notice them, I don’t have the context that would make them salient to me.

Where I just saw some boats, you would see barques and barkentines, schooners and brigs. You would see the tell-tale artifacts that result from using volumetric grids to approximate the Navier-Stokes equations. You would see cuff widths and ruffles, collar heights and lapel angles. You would notice glottal stops and plosive t’s, lumens and resolution and color depth and contrast ratio, establishing shots and jump cuts right where you expect them or, surprisingly, not.

In each case, the trailer would be part of a different conversation, raising and answering an entirely different set of questions, above and beyond the standard ones of “who’s in this movie?”, “what happens in the story?”, and “do I want to see it?”

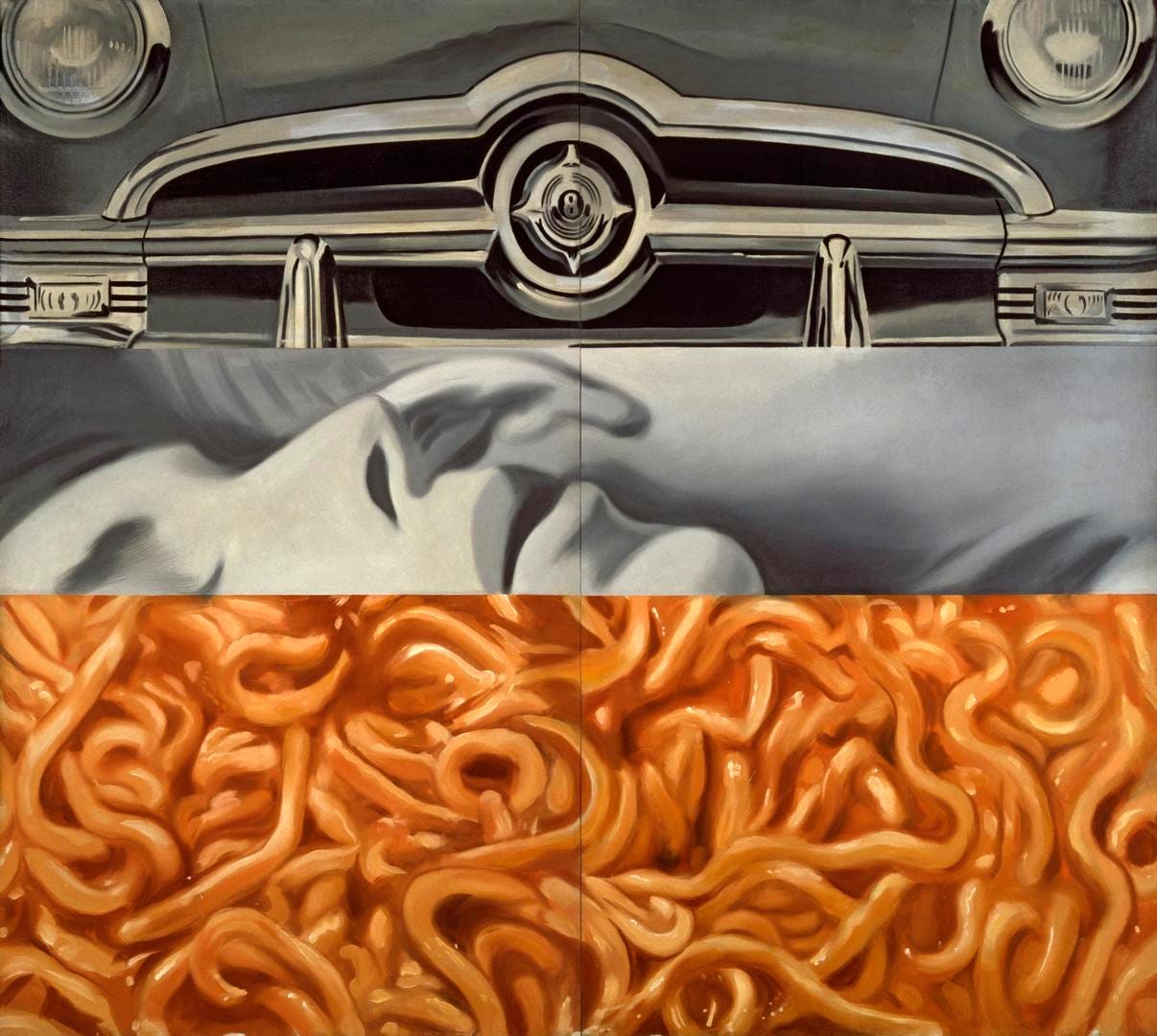

Now do the same exercise but imagine being in a grocery store or a hospital waiting room, imagine being an ad executive, a homeless person, an architect, an actor, a child, a visitor from a distant country or planet, an artist. Imagine each perspective snapping into place like the lenses of an optometrist’s machine. Each snap causing certain objects and details to jump forward into sharp focus while others disappear.

In psychology, the term affect refers to someone’s overall feeling, emotional state, disposition, or mood. In philosophy, it is used more broadly to refer to the connections and attachments we have, or could have, to objects in our environment and the way those relationships are expressed in our bodily experience.

But psychology and philosophy are just subdomains of computer science now. So I propose we examine affect as a type of protocol, a method of formatting and processing data. Your affect, your attitude, your stance in relation to the world, determines the signals you receive from your environment, and shapes the information you are able to extract from it.

We can see the world as data, but we must remember that it doesn’t come that way. Data is constructed, it is manufactured by instruments and conventions, and, for humans anyway, affect is a central component of how the world becomes data to us, how the world communicates with us, how we perceive it, make models of it, learn from it.

Affect, in this regard, includes your mood, your emotional frequency, but it also includes your projects, your commitments, your interests, habits, hobbies, profession, relationships. These things combine to create a dynamic, multi-layered sensory apparatus that organizes the infinitely ambiguous stuff of the world into an ordered array of objects, patterns, and ideas that can be noticed, observed, and understood.

Like all protocols, the protocol defined by your affect is a trade-off. It allows for the transmission of certain objects, patterns, and ideas, and filters out others. Unlike HTTP or SMTP, your affect isn’t compact, fixed, and precise, it is messy, organic, evolving. It wasn’t designed, but it isn’t entirely beyond our control. The fact that we can imagine it taking on different forms shows that we have some influence over it. And how would we change it if we could?

I’ll tell you what I want. I want it all. I’m greedy. I want to see everything. I know this is impossible. I know that to see anything at all means to see some things and not others. Still, the heart wants what it wants. A loss minimization function can dream can’t it?

One of the challenges of hacking your own affect protocol is that its primary dimension is valence — the dimension of good/bad, love/hate, approach/avoid. It’s obvious why this would be true for the sensory functions of any living creature, evolved or designed — to exist at all is basically to prefer some arrangements of the world over others. “You can’t get an ought from an is” they say. What they don’t tell you is that you can’t ever pry the two apart either.

Maybe the ability to see requires wanting to see some things and not others. Maybe we can only perceive the world when it is splayed out against a graph of fear and desire. Not just because we evolved to see, and avoid, tigers (although we very much did) but because, on a much more fundamental level, the whole idea of a signal starts with a particular arrangement of chemical gradients in a cell’s environment and the vibration of cilia orienting and propelling the cell, towards or away from. Affect begins here. We didn’t start by modeling the world and then discover there was a sandwich in it. We started with the sandwich and the world came along for the ride.

But now that we have the world, do we still need to hang, quite so tightly, onto fear and desire, disgust and pleasure? What if we just had desire and pleasure? Wouldn’t that be nice? Or would that break the spell?

Pick up a large rock and turn it over. The underside is a writhing mass of wriggling insects. Yecch. Now dial up the affect of an entomologist, like Trinity, in the Matrix, downloading the helicopter pilot app. There’s no danger here, no discomfort or disgust, just fascination, enthusiasm, and the potential of discovery.

Why do we find boring business meetings so painful, and a lonely pond at sunset so pleasing? Is the croaking of frogs really that much more interesting than the chirp and drone of middle managers discussing quarterly reports? Why can’t we see this, too, as nature sorting itself into delicate, complex, semi-stable equilibria?

Is it that we are in danger of forgetting that we shouldn’t eat contaminated food? That boring business meetings are bad? Really? Do you think that, if I gave you the superpower of appreciating the pond beauty of business meetings, you would spend all your time in them? Of course not! You would be too excited to try out this superpower on museums and libraries, on kindergarten concerts and family reunions and busy street corners and starry skies and lecture halls and crowded bazaars and lonely ponds!

If I could guarantee you that the knowledge that bug-repulsion and meeting-hatred is trying to teach you is safe, that you could retain all the benefits of fully understanding the problems they point to, while, at the same time, seeing them more clearly, understanding them more deeply, wouldn’t you take that deal? Won’t you learn better once you start learning because you love to learn, not just to avoid punishment?

Here’s another kind of valence trade-off: do I have to hate dumb stuff? If I learn to appreciate fine wine, say, does the cheap stuff, which I used to enjoy, have to taste bad to me now? If so, that seems like a bad deal. I get that, given the opportunity, once you have the capacity to appreciate the good stuff — the more complex, subtle, refined, whatever — you should steer towards that. But a lot of the time it’s not your choice and you find yourself in a situation where drinking the cheap stuff is your best current option. Does it have to taste bad to you now? Wouldn’t your life be strictly better if it didn’t? If you could have all the benefits of enjoying the good stuff at the highest level, the ability to distinguish all the subtle differences, and appreciate exactly how they work together to create a sublime experience, and still love the cheap stuff? Really love the taste of it?

Also, isn’t that the kind of person you want to be? Like Nick Charles in the Thin Man movies, moving effortlessly between the rich snobs of high society and the crude slobs of the underworld and never not having a good time, never not enjoying the company.

I guess it’s possible that without the spur of distaste driving us away from the cheap stuff we would never bother. But isn’t the lure of the good stuff enough, on its own? Isn’t it enough to know why all our friends hate Skrillex? Do we also have to be the sad guy standing in the corner at the party who refuses to dance?

As someone who plays poker, I can’t really enjoy the poker scene from Casino Royale. It’s meant to show James Bond’s skill at the psychological metagame of poker, but really he just gets dealt the nuts when his opponent has a very strong hand. Literally anyone would get all the chips in this spot. My poker knowledge allows me to see and understand aspects of this scene that would otherwise be opaque to me but it also just kind of spoils it.

I think my inability to enjoy this scene is a mistake, it dulls my ability to appreciate the lighting, the set, Daniel Craig’s performance, the fluid cinematography of Phil Méheux, the complex choreography of explanation that makes the game legible to non-players, the way replacing Baccarat (from the book) with Hold’em subtly changes the meaning of James Bond as a character. I want to be able to see this scene as a fan who loves it, who knows how to love it, and also be able to see it as a sophisticated film connoisseur for whom it is, perhaps, just another example of formulaic, big-budget, Hollywood filmmaking (but what a nice example!) I want as many of these perspectives as I am capable of processing available to me, because they are all ways of getting information out of the scene.

Ironically, if I were trying to create an AI system that could see, and reason about, the world more effectively (and who says I’m not!) I would be trying to find ways to inject more of this kind of embodied, valence-laden affect into its perceptual apparatus. But thinking about my own experience in light of machine learning, personally, I want less.

Protocols are never private affairs, of course. They are, by definition, shared agreements. Consider this my proposal, not for sweeping changes, but for an incremental adjustment that I believe could yield dramatic improvements. Mostly, consider it yet another re-statement of the fundamental message of this blog: aesthetics matter.

I noticed this phenomenon after learning how to knit. I told a friend that sweaters in a store were “screaming information at me,” which is an insane-sounding way of putting it, but it was just pretty neat how I could *see* all this information I didn’t know was there before, about fiber content, construction techniques, etc.

"Ironically, if I were trying to create an AI system that could see, and reason about, the world more effectively (and who says I’m not!) I would be trying to find ways to inject more of this kind of embodied, valence-laden affect into its perceptual apparatus." I think this is exactly what people do when they assign a persona to a chatbot (e.g., "you are an expert at Jungian dream analysis. Last night I dreamt that..."). The persona seems to more effectively "constrain" the statistical space of token prediction, often improving output quality. It's possible that we're all socially encouraged to do this, take on expertise that implicitly narrows our affect in order to improve the quality of our labor output. The humanities sort of acknowledge this by (ideally) broadening our conceptual space and supposedly enriching the experience of life (before eventually being pushed into expertise). To that end, seems like market forces might be a drag for humans and for AI.