If you haven’t taken Astral Codex Ten’s AI Art Turing Test, you should. The quiz is fun, and interesting, and a good excuse to look closely at a bunch of images and think about them. The picture-making capabilities of contemporary AI continue to be a shocking fact that’s hard to wrap your head around, and whose larger repercussions will take a long time to unravel.

I like Max Read’s take on this, which is to point out that what this quiz actually measures isn’t people’s reaction to art, but people’s reaction to a series of jpegs, stripped of all context. Why does this matter? Max makes the point that the experiential qualities involved in looking at art matter, the concrete, embodied qualities of art as physical objects in actual spaces. I think this is true, but it’s one part of a larger, more general truth, which is that art isn’t just some pictures, art is a project.

This is true, in a particular way, for art of the last century or so, ie. modern and contemporary art. But it’s also true for all of the centuries before that, going back to the first prehistoric cave paintings. Art is not a single project, it’s a range of different, overlapping projects from different eras and different places, but in every era, and in every place, art is the kind of thing that some people get involved with, and pay special attention to, in a specific way. And, from this perspective, the meaning and purpose of an individual work of art is inextricably linked to its context, to the situation within which it was created, to the other works that came before, beside, and after it, and which form a larger conversation of which it is a part. This is true of 18,000-year-old bison drawings, Renaissance church frescos, Dada collages, Warhammer 40k fanart, and everything else.

To be fair, this is probably part of the reason why people who aren’t into modern and contemporary art don’t like it - “Why do I have to pay attention to a bunch of complicated contextual issues that I’m not interested in? Why can’t I just have some nice pictures I like to look at?” Which, fair enough, but that’s a very different complaint than the one implied, or made explicitly, by most of these critiques, which is that the whole thing is either a big waste of time or actively making our shared visual environment worse.

Max also makes the (related) point that it isn’t surprising that people like pictures made by AI (even when they claim otherwise) because most people have bad taste. Most of the AI-generated pictures are kitsch, and people like kitsch.

Scott Alexander has sort of seen this argument coming:

…it also seems very human to venerate sophisticated prestigious people, and to pooh-pooh anything that feels too new or low-status or too easy for ordinary people to access - without either impulse connecting with the actual content of the painting in front of you.

The implication being: “fine art” is mostly a scam. A way for elitist snobs to maintain a smug, self-congratulatory clique which presents itself as doing something profound and sacred but is, in fact, mostly just engaged in maintaining its own exclusivity through a series of codes and signals that are so arbitrary that, when push comes to shove, they themselves can’t even distinguish them from noise.

Ok. Well, he’s not wrong. Or rather, he is wrong, but he’s got a point. In fact, this is a point that has, in one way or another, been at the heart of art as a project for over a century, wrestled with by the very people who make up this clique, and for whom these codes and signals, and the profound and sacred activity they represent or simulate or obscure, have become a subject of endless, obsessive, self-critical fascination. How else do you explain Jeff Koons? How do you explain Andy Warhol?

When you look at art as a project, you recognize that Koons, and Warhol before him, and Duchamp before him, were themselves wrestling with the kinds of questions raised by this very quiz, questions about the relationship between art and jpegs, between what art purports to do and what it is actually doing, between the serious pursuit of profound and sacred truths and a speculative market in tax-avoidant ultra-luxury hyper-objects, between tacky, obscene wealth and abject, hipster coolness, between looking as optical experience and looking as social ritual, between a bunch of recursive, cerebral puzzles about the structure and limits of meaning and a bunch of pictures that may or may not make you feel a special tingle in the bathing suit area, between philosophy and decoration, between what kinds of image-making can and can’t be automated, between the irreducible particularity of the trembling human hand and the generalizing universality of formal symbol manipulation, and the capacity of either to gesture at, point to, grasp, or transmit, the infinite.

Art skepticism seems to be a common stance among a lot of rationalist and rationalist-adjacent thinkers. This general attitude ranges from Scott’s sincere attempt to carefully think through his skepticism (he followed up his AI art quiz with a post about modern architecture and a discussion of artistic taste) to Zvi Mowshowitz proudly declaring he would never set foot inside the MoMa and bluntly proclaiming that “an entire culture is being defrauded by aesthetics”.

I care about this because I like these thinkers, and I think they’re missing something important and valuable about art. I would like to be able to defend art, fine art, modern art, as a project, in terms that they would find convincing, but I haven’t figured out how to do that yet.

Perhaps, as a preliminary sketch of such a defense, I would start by calling attention to the dynamic nature of art - its necessary and unavoidable restlessness. Every work of art is both embedded within a process of perception, reaction, evaluation, and interpretation, and also an intervention into this process. Think of, at a basic level, the relationship of an artist to their audience, the artist’s desire to make something that is both genuinely new and recognizably good, the audience’s desire to see something they can understand and appreciate and, at the same time, their aversion to the formulaic, the rote, the predictable, the corny. This is the process at the heart of creativity, a process which, by its very nature, is recursive, dialogical, even, in a way, adversarial. And it is deeply relevant to a number of important issues within the general scope of the rationalist project as I see it - the reach and limits of formal systems, our ability to recognize, avoid, or extract ourselves from collective traps in behavior space, the origin and evolution of values, value drift and meta-values, coherent extrapolated volition, prediction markets, the alignment problem, all of the complicated theoretical and practical questions about how to make a loving, joyful, interesting world without using lies, and superstition, and fear. How to be embedded in a system and, at the same time, outside of it, looking in and looking out.

Here is the actual paragraph from Benjamin’s Theses on History, written in 1940:

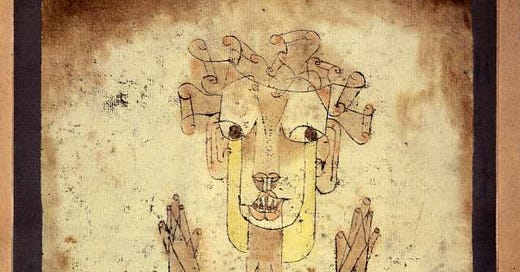

There is a painting by Klee called Angelus Novus. An angel is depicted there who looks as though he were about to distance himself from something which he is staring at. His eyes are opened wide, his mouth stands open and his wings are outstretched. The Angel of History must look just so. His face is turned towards the past. Where we see the appearance of a chain of events, he sees one single catastrophe, which unceasingly piles rubble on top of rubble and hurls it before his feet. He would like to pause for a moment so fair, to awaken the dead and to piece together what has been smashed. But a storm is blowing from Paradise, it has caught itself up in his wings and is so strong that the Angel can no longer close them. The storm drives him irresistibly into the future, to which his back is turned, while the rubble-heap before him grows sky-high. That which we call progress, is this storm.

Later that year, on the verge of escaping to the US, he was told by the Spanish police that he would be deported back to France, and handed over to the Nazis, and he killed himself.

Whimsical, yet profound.

Max Read also points to a related recent study about AI-generated poetry. Like AI art, people can’t tell the difference, and, in a blind test, they prefer it. Here’s the AI poem that was rated most highly by the study participants:

I hear the call of nature, the rustling of the trees,

The whisper of the river, the buzzing of the bees,

The chirping of the songbirds, and the howling of the wind,

All woven into a symphony, that never seems to end.

There’s no way Scott Alexander, who is a very good writer, doesn’t recognize the badness of this poem. Even if discussing and explaining this badness requires some problematic assumptions about being interested in and paying attention to a bunch of issues related to poetry, and writing in general, as a project, as opposed to just the sorting of words into different arrangements which may or may not generate a positive emotional response.

The problem of corniness isn’t just a status game played by elitist cliques, it is also a significant, non-trivial problem. A problem about what it means to be a certain kind of self-perpetuating system, one that is both the result of a bunch of billiard balls colliding, and also, sometimes, the player who lines up the balls and decides what shot to take.

We are both the result of, and responsible for, our own taste. This is a paradox. If you pay close attention to how your own taste operates, you can sometimes catch yourself deciding to like a thing. Sometimes this is because your friends like it, or some cool person you want to impress likes it. But other times it’s because part of you, a good part, a part you trust, recognizes something in the thing, a missing piece for a new person you are in the process of becoming. You say to yourself “I want to like this thing because it is the kind of thing that the kind of person I want to be likes”. And you put yourself in the right posture to like the thing, build the necessary literacy, make the ritual gestures. But you can’t make yourself like something. Often, your existing preferences, as they already are, stubbornly refuse to budge. And sometimes they don’t.

If you pay close attention to this process, you will eventually see this as the terrain of artistic taste. Not your existing preferences, but this ongoing evolution, this back and forth, which Nietzsche called self-overcoming, but we could also maybe just call “becoming”, a process that is both deterministic and open-ended, a process that does not take place inside of you, or outside in your environment, but at the threshold between. Art is one way of paying close attention to this process. Is it a mess? Absolutely. That it works at all is a miracle.

For me, these problems, the problem of artistic taste, of corniness and kitsch, of vibe, the problem of poetry and painting, or the problem of poetry and painting as problems, the kind of difficult poetry and painting in the modern mode that Tom Wolfe hated — over-theorized, fashion-mad, intellectual style-games, wings bent backwards, caught in the howling vortex between a dead god and the atomic bomb — these problems are all deeply related to the alignment problem, writ large. The problem of where, in a material world, meaning comes from, and where it is going. The problem of computers, and software, how to use them, how to survive them. The problem of recognizing the thing that isn’t us yet. The still-unanswered questions of the 20th century, questions about rationality, civilization, and the enlightenment project. How did we fuck it up so badly? What would it look like to get it right?

I think the results of both the AI art and AI poetry surveys might be getting read backwards, and that most people think most artists and poets are making garbage, and so are easily able to believe that humans are making the garbage that is coming out of an AI; educated / erudite commenters who are pointing out that it's of course so obvious that x thing is made by a human are just familiar with that kind of art's contemporary conventions and really aren't any better able to identify what will be long-term valuable to human culture than any random person. Maybe.

There are *many* things to take away from the ACX test and all the articles/thinkpieces it's spawned, but the one to occurs to me is that a lot of the anti-AI people are severely underrating JPEGs - a lot of artists' aims are better served by computer files than physical canvases. Collectors' aims, not so much. ("Collectors" in this case meaning "money launderers who moonlight as aesthetes," because pretty much anyone can make a collection of digital art by right-clicking.)