Bridge

Notes on a game that is too hard for me.

In my house, every evening, before going to bed, we engage in a strange ritual. We watch two men play a game we barely understand. Then we look at each other and shake our heads - what was that? Sometimes we point at the TV and make noises, like the monkeys shrieking at the monolith at the beginning of 2001: A Space Odyssey.

The two men are Rob Barrington and Gavin Wolpert. And the game is Bridge.

I like complicated games. I especially like the experience of watching other people play them, in which the effort you expend trying to understand what’s going on allows you to appreciate, vicariously, what’s happening in the mind of the player, like the toy steering wheel that lets Maggie Simpson pretend she’s driving the car.

I like finicky, highly-technical M:tG control decks, I like watching people try to pull off a clandestine finesse in Hanabi, I like hearing Levy Rozman rattle off opening variations as if they were 5-dimensional origami instructions, I like it when console gamers get out the MS Paint, I like when players build computers inside a game that can run the game they are inside of, I enjoy thinking about the Pretzel Conundrum.

And I’m here to tell you, none of that stuff can hold a candle to Bridge. This is the real deal. Bridge is so galaxy-brained deep, so scarily complex, it makes every other game look like Uno. And yet, for the most part, no one seems aware of this fact. Bridge, having been super popular approximately one lifetime ago, is now in a kind of cultural trough, embedded in a constellation of signifiers that make it a weapons-grade antimeme. But not for long. Mark my words: Bridge will return. It is too good. Too weirdly, uniquely beautiful. And when it does return, when you and your hipster friends start arguing about five-card majors over your bottomless mimosas, the people who run my estate will link to this post and say: See? He told you!

So what is it? What makes Bridge so amazing? Well, the thing that makes it amazing is also the thing that makes it difficult to learn and hard to understand - Bridge, Real Bridge, Contract Bridge, the game that Rob and Gavin play, isn’t just a game, it’s a nested stack of tightly interconnected metagames.

On level zero of the stack you have the basic structure of a trick-taking game. You know the drill - someone leads a card, everyone else has to follow suit, the person who played the highest card wins the trick, and gets to lead the next trick. This is the logic puzzle at the heart of the game, and everything else is built on top of this foundation. Bridge is a partnership game, so solving the trick-taking puzzle involves weaving back and forth between your and your partner’s hands, while dodging the cards in your opponents’ hands. Ok, cool.

Things start to get interesting during the auction. In the auction, we take turns declaring how many tricks we think we will be able to take, given that a particular suit is “trump” (wins even if it wasn’t led). The auction is explicitly “meta” in the same way as betting in Poker and the doubling cube in Backgammon, it’s a kind of thermodynamic trick for taking a game with randomness and squeezing order out of it. You are presented with the game’s core logic puzzle in a randomized state and asked, not just to find the best move, but to predict the various ways the puzzle could unfold, to model the whole puzzle in your head, to picture it as a series of phantom branches forking off into the future, and make a strategic evaluation of that overall picture.

A game’s core logic puzzle has to have the right level of complexity to support this kind of metaplay. The core logic puzzle in Chess is too complicated to be folded back on itself in this way. And so Chess, as beautiful as it is, is really just a big puzzle. Bridge is a strategy game in which Chess-like logic puzzles are the pieces.

But we’re just getting started. Because, remember, Bridge is a partnership game, so during the auction, we aren’t just declaring how many tricks we think we will be able to take, we are communicating to our partner (and, unfortunately, our opponents) about the content of our hand. In the Bridge auction, the series of escalating bids is a tiny language in which each statement is both a move in the game - a binding commitment to a particular arrangement of specific game variables - and, at the same time, a comment about the game - a way of coordinating our actions with our partner to find out which arrangement of game variables would be optimal for us.

Every bid in a game of Bridge is overloaded with this double-meaning. In linguistic terms, every bid in Bridge is a speech act with concrete effects (like saying “I do” during a wedding ceremony or uttering the special word that triggers a magic spell) and a signal by which we mean to send information from a speaker to a listener. It is both of these at the same time. More than anything else, Bridge is about this double-meaning. It is about the intricate dance of information and action by which we say things about the world and do things to it.

This is the source of the game’s turbulent, never-resolved tension between the natural and the artificial. Sometimes you say “2 clubs” because you have a bunch of clubs, and sometimes you say it as part of a pre-arranged code that has nothing to do with how many clubs you have. Serious Bridge is built around these codes, every partnership uses an elaborate bidding system that allows them to signal in this way. And they’re public knowledge, by the way. You aren’t allowed to have a secret system.

So far so good. But everything I’ve described so far is true of Bridge as it already existed up to the mid-1920’s, which is when it got really good.

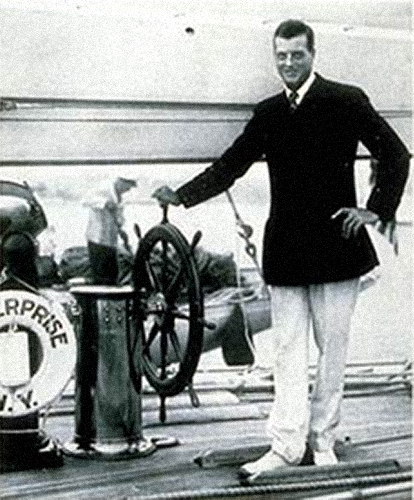

In 1925 beloved yachtsman and all-around rich guy Harold Stirling Vanderbilt released a scoring system for Bridge that transformed what was already a fantastic and very popular game (Auction Bridge) into a brilliant masterpiece that became a world-conquering pop cultural phenomenon (Contract Bridge).

What did he do? Well, we are rapidly entering a zone beyond my pay grade. But, as I understand it, the scoring system Mike came up with (yeah, his nickname was Mike) made bidding matter. It amplified the consequences of bidding so that you were rewarded for bidding in the most precisely accurate way and punished for deviations from this accuracy. This incentivized a greater focus on the load-bearing capacity of bidding as a communications channel and encouraged players to explore its potential as deeply as possible, leading to the complex bidding systems that we have today, and the rich strategic space that goes along with them.

(I always think of Mike Vanderbilt alongside Lizzie Magie and Alfred Butts as one of the great unsung heroes of early 20th-century game design. Before it was a profession, game design was done by inventors, tinkerers, radicals, and dilettantes - three cheers for these beautiful weirdos!)

If the auction folded Bridge over itself, to squeeze out more structure, more pattern, more information, the scoring tweaks that created Contract Bridge folded the game again, doubling the significance of every detail of player choice and action. And the competitive format that evolved around this game became yet another twist designed to wring out the last remnants of noise from the randomness of the shuffled cards. The highest floor in the metagame stack - Duplicate.

In Duplicate Bridge everyone gets the same cards, and your actual score is the difference between how many points you made and how many points all the other players made in the same situation. It’s as if Bridge players looked at Poker, in which the cold white peaks of good decision-making gradually emerge from the uncertain mist of random variance over a long, slow run of thousands of hands, and said “We don’t have time for that. We’re going to die soon!” So they made the long run happen all at once, in a single afternoon, by giving every hand, every random distribution of cards, lucky or unlucky, to a hundred different teams at the same time, and stack ranking the results. A duplicate Bridge tournament is sort of like a computer program for determining the best way to play a set of hands, in real time.

Which brings us back to Rob and Gavin. The format that these guys play, the one we watch every night, is a special kind of duplicate tournament. Now, you might have thought that we’ve stretched and folded this taffy as much as possible, but there’s one more twist coming - bots. In this format, every player is an individual who plays with a bot partner against two bot opponents. All of the bots are the same algorithm, using the same bidding system. On the one hand, this reduces variance even further, squeezing yet more randomness out of the system. On the other hand, it adds an additional layer of technical skill to master - knowing exactly how the bots “think”.

Bots! As if Bridge, this twisted knot of predictive modeling, protocol hacking, and information theoretical meta-puzzles, needed another cyberpunk ingredient to make it the most 2024 possible game. Now it has bots in it!

Bridge is a game that is breathtakingly dense. We tried learning it a few years ago, back when we were young enough that it was “cute” that we were into it, but it was just too hard for us. And now, even if we did know it, we would just be two old people who are bad at Bridge. But no one can stop us from watching it on YouTube.

Every hand opens the same way, with a glimpse of the familiar puzzle that starts with 13 cards. We count the points - 4, 8, 11, 14, 15 - this much we remember, but already Gavin and Rob are miles ahead. Rob with his FM-smooth drive time baritone, and Gavin stopping and starting like a free-jazz soloist chasing a fleeing melody. Back and forth they speculate about the distribution of the unseen cards based on the bids being made, hypothesize about most- and least- likely universes, spin out scenarios and counter-scenarios, race like wildfire through thickets of logical deductions that would have taken us hours to navigate, and then stop dead to ruminate in excruciating detail on a decision we wouldn’t have seen at all, whose significance we can barely fathom.

Sometimes, because of the tournament structure, they’ll choose to take a line of play that is less likely to lead to the best outcome, because, in order to win, they need to do something different than what most other players are likely to do. Which is, of course, a beautiful example of donkeyspace in action.

Once, about a lifetime ago, America was obsessed with a dense, complex, abstract strategy game, obsessed. This unforgiving, cerebral, hard-as-nails game was more popular than Wordle, more popular than Pickleball, more popular than Minecraft and Among Us and Fortnite combined. I find this fact amazing and inspiring. There is an appetite for such things. Under the right conditions, we will decide this is what we want to play - a game that invites us to bend and stretch our minds into surprising new shapes as we try to solve the hardest problems we can think of, together.

This is brilliant... Except for the bits about it being too hard...

Are you aware that most clubs run lessons, and they start with the basics, and over time you build on it and become better the more you play and discuss with others - the advantage of duplicate meaning that at the end of the day, everyone's played the same cards, so the debrief at the end is meaningful and constructive.

Sincerely, an avid Bridge player since 2009 when my youngest started kindergarten.

I LOVE it. It's played on many levels. There are social players, locally competitive players, nationally Competitive players, internationally Competitive players, and professional players.

Find your national bridge association, they'll put you in contact with your nearest club, and they'll let you know when the next set of lessons start. In New Zealand it's NZBridge.co.nz

fab writing - i still don’t really understand Bridge but i think that’s to be expected :)