Fractal Block World

Or, How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love Video Games Again

I’ve had a weird relationship with video games recently. A long time ago it became obvious to me that they were the most important and interesting domain of pop culture. After all, video games are software as an artform, interactivity for its own sake, an exploration of the things that make computation not just useful but beautiful and meaningful. Video games are amazing, both viscerally, as experience machines, and conceptually, as possibility spaces. As the intersection of games and computers, they combine our distant past - ancient rituals that pre-date civilization, with our far future - kaleidoscopic glimpses of the various directions in which our world might go.

I still feel that way about video games. I’m just not sure I like them. I mean, I like some of them fine, and a few of them I’m absolutely crazy about. I still think AAA games are something like modern-day cathedrals - sublime monuments of creative engineering, and I still think indie games have plenty of interesting experimentation, if you dig for it. But, overall, I just have this vague feeling of dissatisfaction, a general sense of malaise about video games as a… whatever it is - artform? Hobby? Lifestyle?

Look, I’ll admit upfront that this might just be me. Maybe video games are doing great. Maybe they are vibrant and healthy in all the ways you might want your artform/hobby/lifestyle to be, and maybe I’m just personally feeling burned out. I wrote a book (still available!) which was my attempt to articulate what was beautiful and important about video games and games in general. I stepped down as Chair of an academic program devoted to the creation of video games as a creative discipline. Maybe this is just me decompressing from having spent so much time and energy being an advocate for video games, being the guy that says “Hey - these things are so much cooler and more interesting then they look.” Maybe this is just a reversion to the mean.

Or maybe this is what it always looks like from the inside of an artform/hobby/lifestyle. Maybe musicians and filmmakers are exhausted and disappointed with the status quo of their domains, and look at video games the way I look at music and film, thinking “I wish we had a bit more of that energy going on.”

So, for whatever reason, I spent most of 2024 feeling a bit alienated and out of touch with video games. Then, at one point, I started watching Petscop, a YouTube liminal horror series from 2017 that takes the form of a bunch of let’s play videos of a fictional game. And this subtly inflected the YouTube algorithm in a way that it started showing me Minecraft content. And I watched some, and it really lifted my spirits!

Minecraft, with its minimalist, techno-cubist, proc-gen pastoralism, is a great-looking game. And somehow, over the past decade and a half, it has managed to keep a lot of what made it weird and interesting and beautiful to begin with. I watched the last two hours of a guy walking to the Farlands, the place where, because of its distance from the origin, the math that produces the landscape starts to break down. A trip that took him 7 years to complete.

I watched some competitive Minecraft, and was surprised to learn how much of Fortnite’s maniacal bildungskombat was in there. I watched some of the theorycrafting and server lore that populates the Minecraft content ecosystem. And I just generally enjoyed learning that this game, which I had mostly ignored, had not turned into a cesspool of software-as-a-service garbage. It made me happy that the place a generation of kids had grown up inside of seemed like an ok place to grow up inside of. That it was, like many video games, cooler and more interesting than it looked. And it made me think - chill out, video games are doing all right.

And then, because of this new found Minecraft enthusiasm, the YouTube algo served me up a video of a game I’d never heard of. A game called Fractal Block World. And then I played it, and I loved it, and it reminded me of all the things that are great about video games.

Fractal Block World was made by a small team led by developer Dan Hathaway. Hathaway was college friends with Zach Barth, and, back in 2007, worked with him on the game Infinifrag, which eventually became Infiniminer, which is the game that Notch turned into Minecraft. You can think of Fractal Block World as a kind of distant cousin of Minecraft, a splice taken from the same root and cultivated in such a way that it grew in a totally different direction - not towards accessibility and comfort and charm, but towards the thorny mindfuck aesthetics of games that explore the unconventional metaphysics of simulated space, games like Manifold Garden, Maquette, or Miegakure.

FBW is an exploration game set in a world in which space is represented fractally. You can shrink down to smaller scales, and when you do, you see that an object that was a single block when you were bigger is now made up of a complex arrangement of blocks and spaces. Continue to zoom, and you will discover that these smaller blocks are themselves not solid, they, too, are complicated 3D constellations of blocks and spaces.

Imagine looking at a sugar cube, and then shrinking down until this cube was an enormous, greebled Borg mothership, full of interlocking chambers and passageways. You thread your way through this ship, carefully avoiding guards, until you find yourself in a small room with a bunch of little objects scattered across the floor. But no, keep shrinking, and these objects reveal themselves to be vast structures, massive ziggurats, towering over a desert landscape that stretches to the horizon in every direction. Keep shrinking and the immense door of the ziggurat before you becomes a sheer cliff face that disappears into the mist far below. The cliff is riddled with openings to a twisty cave system filled with monsters and treasure. Wait, weren’t you trying to get through this door? Now you are deep inside of it. The room you entered ages ago is a fading memory, the ship an ancient myth, the sugar cube… wait - what the hell was in that sugar cube anyway?

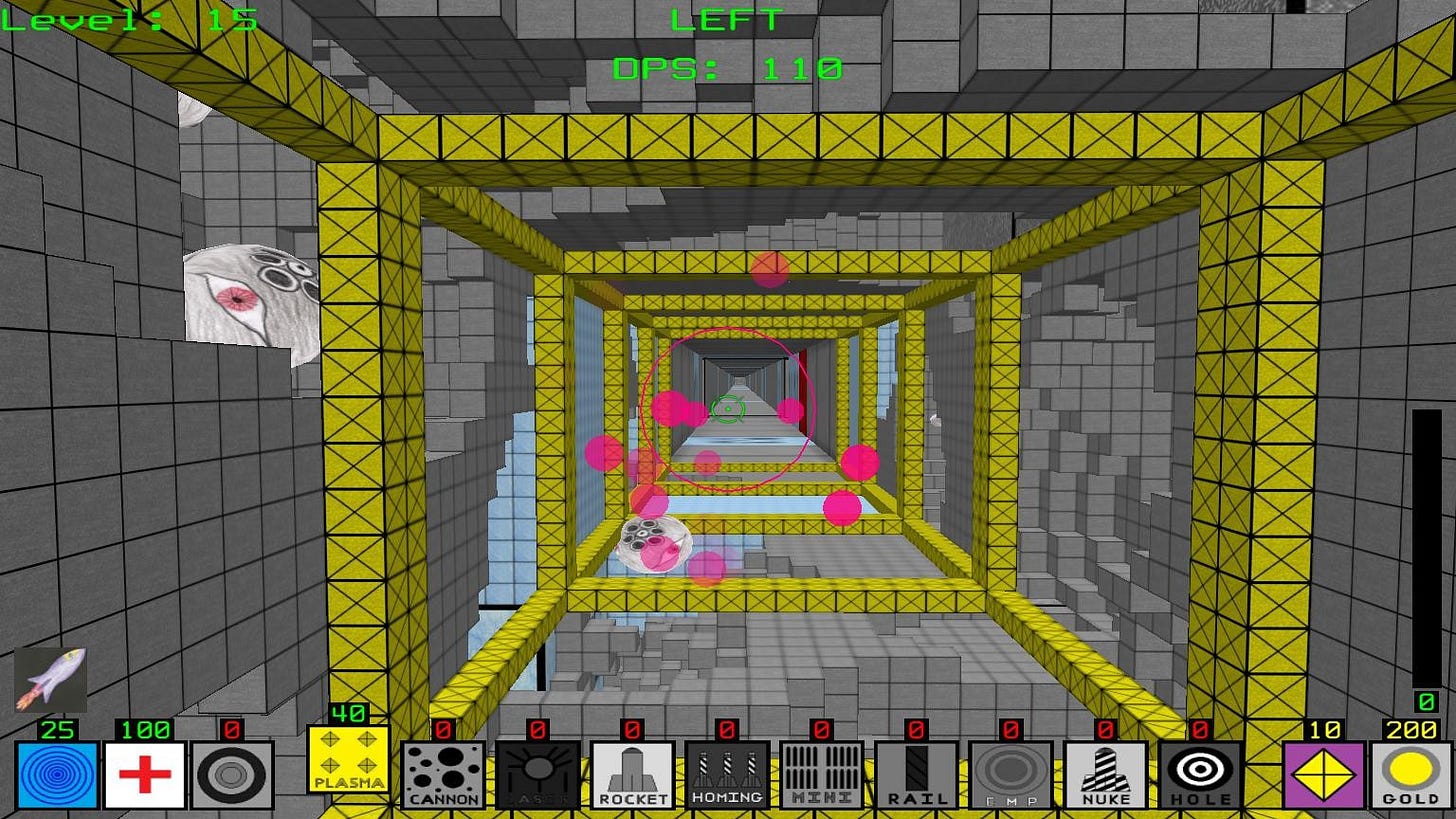

Using this core engine, Hathaway has created an enormous, sprawling open world to explore, which you do so from a first-person perspective, in a ship with six degrees of freedom, similar to the classic 3D action game Descent. Like Descent, this world is filled with swarms of hostile enemies, and you have an array of weapons with which to defend yourself. But this isn’t an action game, exactly. It’s a game about finding your way through a strange world, understanding its logic, and diving deeper and deeper into its nested, self-similar geometry, searching for a single key buried deep within.

Visually, FBW has a radical, bare-bones simplicity that you might call “programmer art”. But FBW is programmer art in the best sense, there is no pretense or illusion, no attempt to simulate the real world, or a cinematic world, or a cartoon world. The world you are burrowing deeper and deeper into is code. You are inside of software that is unfolding in every direction around you. As a result, the world feels real. A real place made of rules and logic, pixels and math. I found myself believing in this world, and caring about it, and wanting to understand it, in a way that made me stop and think - oh, this is what people who love Dark Souls are talking about.

I experienced, while playing FBW, a kind of delirious dislocation that I hadn’t felt since first playing DOOM. There were times when I was lost, deeply lost, in a way that’s hard to describe. Not only did I not know where I was, or where I was going, I wasn’t sure what it meant to be somewhere. In FBW, space isn’t just fractal, it’s statistical. Places aren’t locations, they are definitions, rules about how things can be. The logical relationships between these rules is what creates the illusion of space that you are moving through, just like how, in the real world, the rules of physics create - wait, I’m not sure where I was going with this.

In a way, every 3D video game has this property. But in FBW it is laid bare, made real, and explored on its own terms, instead of being cloaked in the comforting and familiar illusion of realism.

FBW’s commitment to non-conventional geometry carries over to its interactive structure, the way it organizes the player’s experience through goals and mechanics. Many times, while playing FBW, I had the sense that, despite having all of this standard video game stuff - weapons and enemies and treasure and save points and power-ups - I could not use my standard video game heuristics to figure out what to do next or how to do it. More than anything else, it was this sense of unfamiliarity that I loved, this sense of not knowing, already, what I had stumbled into and how it was going to go.

This world was confusing and mysterious, but not, like in many mysterious games, because a layer of intentional obscurity had been draped over a fairly traditional structure, and not because an otherwise familiar world had been populated with neatly circumscribed pockets of mystery, little problems to overcome in the form of puzzles or combat, but because Hathaway had drilled deep into a genuinely weird and mysterious and scary corner of the universe and sent you tumbling into it. FBW is a game that starts in the Farlands and keeps walking.

Even when I was deeply lost and confused and worried I would never find my way out, it never felt like the result of sloppy or careless design. At every point, I felt like I was in good hands. I felt well taken care of. But not like I was at Disneyland, more like I was somewhere scary and cool with someone I trusted who had found something strange and beautiful and wanted me to find it too. This is outsider art, but it is well-crafted. It feels like the kind of game that was played over and over again during development. In that sense, despite being full of placeholder audiovisual assets, and despite missing the stultifying trappings of “good design”, it feels, in its own way, highly polished.

I read Edwin Abbott’s metaphysical fable Flatland at just the right age to have it blow my mind. It wasn’t just the thought experiment of picturing the geometry of space in a new way, it was also the realization of what literature could do, that it could make the strangest kinds of abstract reasoning vivid and concrete. Now, on the far side of the moebius strip of my life, FBW has hit me with a similar force.

In the late 70’s, the Polish science fiction author Stanislaw Lem complained that most SF, while purporting to offer up tales of the strange and exotic, was, in fact, in the business of domesticating the universe, re-packaging the genuine incomprehensibility of outer space and future technology and alien civilizations into comfortable, familiar tropes. I think, in a similar way, that video games have lost touch with the strangeness of software, with the weirdness of computers, the weirdness of simulating a world with math. FBW is a big dose of this weirdness, and it came along at just the right time, as something always does, to remind me what video games can do, and why I love them.

I am so right there with you. You've been in games much longer than I have, but I think for those of us in the 20+ year bracket, there's been this steadily growing feeling of something fraying and coming apart. (I suppose there are a lot of reasons to feel that way more broadly in the world.) Disconnected. I completely resonate with your comment about having a deep appreciation for the production accomplishment of AAA, and the gem-hunting expedition that is the indie market -- and somehow this leaves a kind of malaise that's a big part nostalgia but something else as well. AND yes, Minecraft! I have such mixed feelings because as an online game operation I'm finding it miserable to work with as a sysadmin for my son's server (and this offends me on some kind of deep level, colored by general corporate animosity) -- but I was just yesterday showing a designer friend the book Minecraft STEM Lab and the profiles of some of the things creators are doing with it independently now. (Like Templecraft! https://www.thespace.org/commission/templecraft/ ) And telling my husband a few days ago that Minecraft servers are today what MUDs were when I was a teenager -- small, intimate environments where the continuum between player and builder was an indistinguishable gradient. We live in an era of ambiguity that seems to approach toxic levels, but congruently the possibility space is richer than it's ever been.

I wonder if you would like this game if you haven’t already played it: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Under_Presents