The Afterlife of Go

Work and Play in the Age of Idiot Gods.

This recent WIRED article considers the potential impact of automation on the economics of higher-paid, higher-status, intellectual and creative work, asking “who will you be after ChatGPT takes your job?” The gist of the article is that we are used to the idea of automation threatening lower-wage, lower-skill jobs, but how will we handle losing jobs that matter to us, not just in terms of financial security, but as expressions of our inner potential and opportunities for achieving respect and admiration? To answer this question, the article looks at the post-AlphaGo career of Lee Sedol, the Korean pro who lost the historical man vs machine match in 2016, and several other professional Go players. The idea being that these pro players represent the “furthest edge of white collar work”, the most advanced form of creative and intellectual labor.

Lee Sedol retired from Go shortly after his defeat, saying "Even if I become the number one, there is an entity that cannot be defeated." But we should keep in mind that he was already talking about retiring in 2013, before AlphaGo existed. Fan Hui, the European champion who also played AlphaGo and lost, went on to join the Deep Mind team and is a co-author of the important AlphaGo Zero paper that came out in 2017. According to the article, Ke Jie, another top pro who played and lost to AlphaGo, “underwent a remarkable change” after his match. Apparently, he went from being a brash and outspoken hothead to adopting “a stance of irony, playfulness, and humility, becoming a much loved crowd-pleaser along the way.”

The article describes Ke’s transformation as a “pivot from ‘best player in the world at humanity’s most logically complex game’ to ‘comedian’” but I don’t know, he’s currently listed as the number two player in the world, and I’m pretty sure they still determine that ranking based on games won, not Instagram followers, so maybe his job hasn’t changed all that much? And I suspect that, to the degree that his job does consist of being an “entertainer” more than it used to, this is probably due to the dynamics of social media in general, and not the presence of superhuman Go software.

Which is not to say that I doubt the psychological, social, and philosophical impact that AlphaGo had on the world of professional Go. Even as a casual observer, I felt the ripples of this trauma. We tell ourselves stories to make sense of the things we do in the world. And when we invent machines that can do things we thought only people could do, we invent new stories to make sense of that. There’s a reason that the legend of John Henry is one of the central myths of American culture. And it was John Henry I was thinking of when I compared Go to a work song in the middle of the night in March of 2016, watching the results come in.

But work songs aren’t work. And playing Go isn’t exactly a real job. There’s something perverse about treating games as work. Work, even when it is deeply rewarding, pleasurable, and meaningful, is something we do in order to accomplish something. And games are something we do for their own sake. Games aren’t just something we do instead of work, they are a kind of anti-work, a ritual in which we expend maximum effort to achieve arbitrary, useless, imaginary outcomes. This is why trying to get kids to study their homework with the same energy they apply to studying Pokémon is like trying to get rocks to roll uphill.

Go isn’t work, it’s a work song. And we pay the people who play it the same way we pay singers - out of a mix of fascination, charity, and gratitude; sporadically; too much or not at all. But economies come and go, and Go remains. Go will almost certainly outlive this economy, and the next one, and the one after that. Please the Emperor. Win the tournament. Stream the content. All of them are bullshit jobs when compared to the timeless avocations: cut, connect, surround.

In 1930, in the midst of the Great Depression, economist Maynard Keynes wrote Economic Possibilities for our Grandchildren, an essay in which he speculated that, in a hundred years (i.e. 7 years from now), technological innovation might create a world in which people didn’t need to work. Would we, Keynes wondered, be able to adapt to such a world, a world where we no longer had to struggle for subsistence? Would we be able to overcome the habits and values bred into us by generations of work and learn to cultivate the art of life itself? For what it’s worth, Keynes didn’t have any grandchildren, but he had plenty of grandnieces and nephews, and they have jobs like neuropsychologist, astrophysicist, conservationist, and historian.

The much-maligned philosopher Bernard Suits wrote a book about this topic called The Grasshopper: Games, Life and Utopia. Work is what we do because we have to, and games are what we do that we don’t have to. Therefore, games show us what we truly value, a window into paradise. But there are two ways to have to do something. You can have to do it in the sense of choosing to do it because you want a specific outcome, or you can have to do it in the sense of your action is the inescapable result of some causal force. Is paradise an escape from want? An escape from cause and effect? It’s hard to even picture such a thing. Games certainly have plenty of both. What else is a game but a particular kind of want and the web of cause and effect in which that want is entangled? [Points at butterfly] Is this the alignment problem?

Game designers know you can’t just make people have fun. You have to get them to pretend to want some stupid thing the pursuit of which causes them to have fun by accident. Wants come from somewhere and lead somewhere else. Utopia is not a place but a process. That’s what I see when I look through Suits’ window.

So how does AI change the meaning of a game?

Before Deep Blue we might have thought that having a superhuman computer opponent would ruin a game. We might have thought back to the way Tic Tac Toe stopped being fun when we discovered the algorithm for perfect play, how that knowledge broke the game’s spell over us and drained it of magic. But it’s been 25 years since Deep Blue beat Kasparov and Chess is doing great. It’s thriving! AI has been integrated into the culture of Chess, giving us new tools for analyzing the game that improve the play of expert players and improve the legibility of the game for casual observers. I just checked Twitch and there are 10 times as many viewers watching Chess as watching StarCraft, a game that AI has only just begun to play well. If we’re lucky maybe AI will ruin that game too!

There was a special aura around Go that made people think it might be especially hard for AI to master. The search space was so large that mechanical, brute-force methods couldn’t plumb its depths. You needed subtle intuition, ineffable pattern-awareness. And maybe good old fashioned monkey brains had some magic in these departments that silicon couldn’t match. Obviously, this turned out not to be the case. In fact, in the age of transformer models, we’ve learned that AI is very good indeed in these departments.

There’s no reason that the culture of Go shouldn’t thrive in the age of AI as Chess has done. It’s somewhat hard to tell how it’s doing because Go has always struggled to find a foothold in the US (a problem I once tried to address by suggesting we should treat it more like an eSport.) As in Chess, Backgammon, and Poker, we should think of AI as a tool for analyzing the game, not as a new breed of opponent that demotes our status to second class.

Still, I sympathize with the Go players, teachers, and analysts who felt they had the wind knocked out of them 7 years ago, and have struggled to regain their moorings. Because it existed at the furthest edge of human cognitive capability, high-level Go had an almost religious significance. It functioned as a kind of sacred ritual of focused thought through which we could occasionally glimpse the divine. To be confronted by a mechanical operation that could see farther through this lens than we could was a disorienting shock, and the fact that this mechanism was itself created by humans was cold comfort.

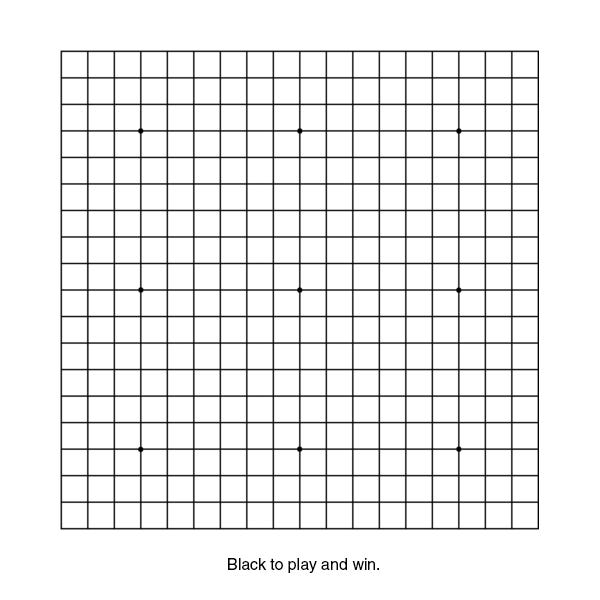

But Utopia is not a place, it’s a process. And it turns out the story doesn’t end there. A couple of months ago, a group of researchers announced that they had discovered a technique that allows an amateur-level human player to consistently beat state of the art superhuman Go AI. What’s amazing about this adversarial policy, as they call it, is that it’s simple to explain and understand. Basically, it involves allowing the AI to surround a group of your stones and then surrounding the group that is doing the surrounding. Because the AI considers your innermost group dead it doesn’t see the threat coming until it’s too late.

The technique works because this is a type of situation that doesn’t often occur “naturally”, and therefore the AI has a kind of blind spot, and misses what would be glaringly obvious to even a novice player. And this blind spot includes the basic principles of life and death the game is built on, concepts that are completely fundamental to how we think about the game. Realizing that the AI is missing these basic concepts totally transforms our impression of it, makes it seem colossally stupid. Like it isn’t actually playing Go at all. It is selecting moves, and its ability to select winning moves is uncanny, godlike. But it isn’t playing a game. It isn’t trying. It doesn’t want. It doesn’t know.

This video by Nick Sibicky is a wonderful demonstration of the strategy in action and includes some terrific commentary. It’s an emotional video, and you can see Nick struggling to make sense of how he feels. He talks about the deep sadness he felt when AlphaGo beat Lee Sedol, a feeling he describes as “the universe was not where I left it.” Now, 7 years later, he is shocked to find the universe has moved again:

Just imagine if we rewound the clock back to 2016 and we were able to feed human players this knowledge. AlphaGo never would have happened. It would have been seen as really cool, really powerful, but not intelligent. It’s a processing tool. Instead of seeing AI as this inevitable endgame that we are currently entering, it would have just been a really smart processing tool, not an infallible God. And perhaps in Go that’s the thing, we have this culture of the “hand of God”, playing the perfect move, the divine move, that idea that if you can know what’s going on on a Go board and play that one move that is divine you’ve achieve nirvana, you’ve transcended something. The last few years we’ve all thought “well, the robots are closer than we are” but then this happens.

If you want to see the hand of God in action, look no further than Adversarial Policies Beat Superhuman Go AIs. This is what it looks like to play Go, to be curious, to have a problem, to want something, and have that want entangled with the world. To wonder, and speculate, and try, and discover. To start one place and end up somewhere else.

And if you want to know about the future of intellectual and creative work, think about this: it took 7 years. And this wasn’t a messy domain full of nebulous trade-offs, ambiguous values, and wicked problems, like, say, blogging or technology journalism. This was a tiny, toy domain defined by a handful of rules, where success and failure are precisely defined and feedback is immediate. And it took 7 years to discover that this thing we thought was a God had no idea what it was doing.

When I talk about Humans v. Machines with my journalism students, I start with John Henry. John Henry and Desk Set.

I disagree with the upshot of the existence of adversarial policies. If you trained alphago on a few of these games, it would easily be resistant to them. So you can only eke out a tiny fraction of wins against the system by using that strategy, after which it’ll continue dominating you. So the real conclusion IMO is like “after losing 1e6 games in a row, you can win like 10 games, after which the strategy stops working, and then you’ll lose the next 1e12 games until you find another trick, etc.”

So you’re still losing like 99.999999……% of the time.