Why I Love SET

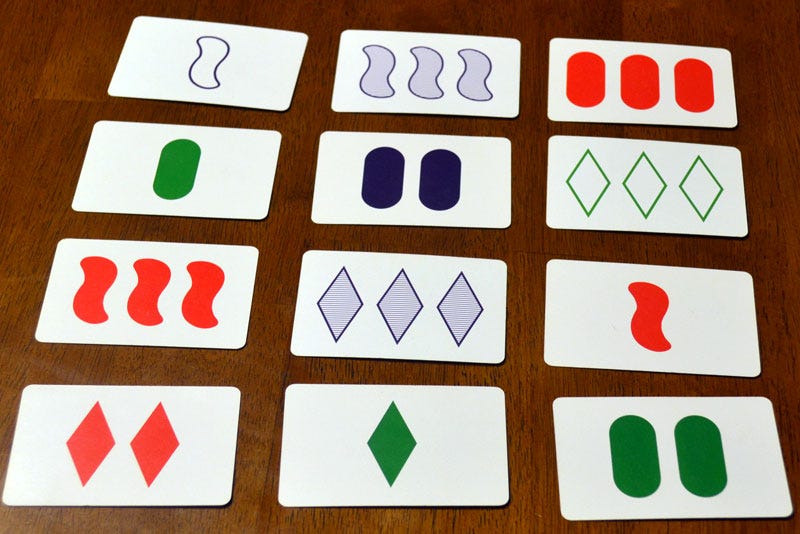

Set!

First of all, the origin story is awesome. Marsha Falco was studying genetics and used cards to help her think through a problem related to how traits are inherited. Each card represented a dog, and had some symbols on it, representing the various traits of that dog. And she noticed cool mathematical properties in the way these symbols overlapped. And it seemed like fun. And it was fun!

SET is also great because it’s a beautiful counterexample to a really strong theory about games - that they are made out of choices. That, as Sid Meier famously proposed, they are a series of interesting decisions. You might awkwardly append, as I often have, “...and actions!” But, even then, you’re in the same boat. Whether you like cerebral, turn-based things or experiential, flowy things, in either case it’s usually a series of things, interacting, unfolding, developing.

From this perspective, you wouldn’t expect a game that consists of pure action to be viable. Like, imagine Baseball, but instead it’s just a ball-throwing contest. For distance. Just that one thing. Or, imagine the game “How High Can You Jump” which is just that.

I realize, as I’m writing this, that I’m describing actual Olympic sports. So, obviously, games of pure action do exist. But you wouldn’t expect a card game to be one. You wouldn’t expect a completely abstract, non-physical game to be a test of one specific skill that doesn’t involve any strategic choices. And you wouldn’t expect a game like that to be deeply absorbing. But it is.

Also, by the way, if games of pure action exist, what even is game design? If “do a thing”, full stop, is a reliable way to experience the sublime, what is all this other stuff? Sometimes I think game design is about finding the interesting corners of the universe where “just do a thing” works. As Falco clearly did. SET works because of its weird and interesting features as a mathematical object. Other times I think the role of the game designer is to point at a random corner of the universe and then just keep saying “you aren’t looking hard enough.”

Anyway, games of pure action do exist, SET is one of them, and it is very beautiful. At no point, while playing SET, are you doing anything except the one action, and trying to do it better. It’s like a single note, or a single, intense flavor, where you go - huh! what’s that? And then it’s that one moment, over and over again. Like Babe Ruth at the ball-throwing contest, you just keep popping back to that same frame where you go - huh! what’s that?

Is that a game? Yes! And what a game!

The thing that gives SET that pop of huh! brainfeel is that the thing you’re doing is perceptual, it is an act of seeing, noticing, finding. But, most of the perceptual things we do are invisible to us, we’re not aware of them, we just do them. The perceptual action in SET is pitched just slightly beyond the things you do automatically.

Seeing that 3 cards make a set is sort of like seeing that something is red, but it’s got one extra twist, where you’re like - huh! ok, ok, I see where you’re going with this. It’s almost automatic but it never becomes fully internalized to where it just happens - uh, yeah, that’s red, what’s the big deal? It always feels like there’s this extra move that you can’t quite fully wrap your head around.

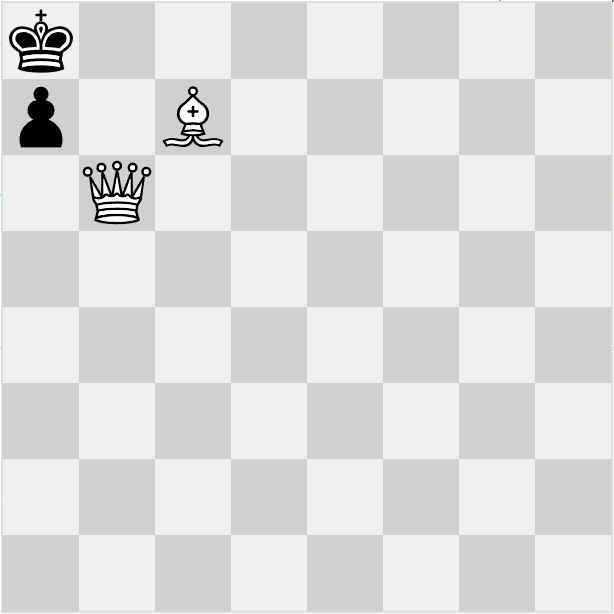

In a sense, seeing the solution to a Chess problem is also a perceptual action.

Finding mate in this simple position is almost just a kind of looking. Almost just a matter of noticing a fact about this particular arrangement of pieces. But it still has an element of logical operation, especially to someone like me, who doesn’t play much Chess. I still have to play out the move in my head and confirm that it works. As opposed to simply seeing it, the way that I see which piece is the Queen.

The action you do in SET, the action of seeing that 3 cards make a set, falls somewhere in between these two cognitive modes, beyond the fully-automatic, instantaneous action of seeing a color, but short of the deliberate, multi-step, if-this, then-that action of seeing a solution to a Chess problem.

The key to SET is that you’re not just doing this thing, you are trying to do it better. You are racing to do it faster and better than your opponents, or, if you play cooperatively, as I do, to beat the clock and improve on your record. So, you are made aware this action in a special way, you notice yourself doing it, and you ask yourself, “why do I suck at this?” and “how can I improve?”

It turns out these are really interesting questions. And the answers are far from obvious. Because one of the first things you notice, as you try to improve your SET skill, is that trying to improve your SET skill can make it much worse. The ability to see a set is one of those things, like throwing a baseball, or hitting a golf ball, where consciously focusing on it can really screw it up. It’s even worse, because those physical actions are complex, multi-step processes, and sometimes breaking them down, analyzing them technically, and making some conscious changes really can help you improve. And that’s not the case with seeing a set.

Getting good at SET is mostly about not stressing out, about remaining calm, getting out of your own way and letting your brain do its thing. When it works, it feels like magic, because you feel yourself getting good at a hard thing, but it’s a thing you aren’t responsible for, that you are not in charge of. The part you are in charge of is making sure that your brain has everything it needs, maybe a cup of tea, some quiet music, and then sitting quietly and not interfering.

Sometimes, when you haven’t found a set in a while, you can feel the deliberate, linguistic, logical, if-then part of yourself start to chime in - “let’s see,” you think impatiently to yourself, “we’ve got these two reds here, so maybe a third red somewhere?” Or, at an even lower level, little numerical and verbal hooks start attaching themselves to cards in your mind, and you can hear a little voice in your head counting, sorting, dividing, like the sing-song sounds of a child learning the alphabet. One, two, three. Red, blue, green.

You must never allow yourself to do this. This is the slippery slope that leads to deliberate, mechanical, operational looking, which, while tempting, is a million times slower than what you are after - the holistic gestalt of instantaneous seeing. So you hush this voice. But quietly, calmly. Because the last thing you want to do is start an argument. Learning how to silence this voice without starting an argument is the main skill of SET.

But the main reason I love SET is the particular way it felt to play, when my wife and I were playing it together on a semi-regular basis. With the iPad on the sofa between us, we played a timed version that gave you more time when you hit certain milestones of sets found, and we tried to beat our record. And doing this well meant coordinating our brains in a particular way, adapting to each other’s rhythm, each of us evolving our own style, our own specialization, without discussing it.

Or without discussing it too much. Because, oddly enough, in the two brain version of the seeing problem, the prohibition on verbalization is lifted, slightly. It’s not that we discussed strategy, we knew instinctively that that would be counterproductive. It’s more that, the chattering parts of our brains, the ones that weren’t allowed to interfere with the seeing problem, were free to talk to each other, to keep each other company. In fact, in some mysterious way this helped the other parts of our brains, the ones doing the actual work, silently, off camera, to synchronize.

So we would, occasionally, haltingly, talk to each other about the shape of the board, what it felt like, whether or not it was weird. In a kind of pidgin English that was the native tongue of the parts of our brains left over when most of our brains were quietly busy, we would discuss the personalities of the cards as they came and went, which ones were eager to join up into sets and which ones stubbornly refused - as if no one had told them the point of the game!

When one of us went on a heater (usually her) the other one would make quiet sounds of appreciation and encouragement. And, when one of us decided to hit the NO SET button (usually her) and got either the sweet chime of correctness or the harsh whinny of incorrectness, the other would make the appropriate sounds of celebration or commiseration.

And so, on many a cold night, with a fire in the fireplace, and something quiet and loopy on the bluetooth speaker (like Arthur Russell maybe, or Domenique Dumont, or some Ethiopian jazz), we would allow ourselves one more, one more? One more. And we got pretty good at doing something that can’t really be explained, something that has to do with being in the right mood without trying too hard, and surfing on the edge of yourself and another person. In a life spent playing games, it was, without a doubt, one of the most intense and rewarding and meaningful game experiences I’ve ever had.

And that’s why I love SET.

This is gorgeous. That moment-to-moment “huh!” you describe is exactly it—like the game is tickling a part of your brain that usually stays dormant, or busy doing more “useful” things. I’ve always loved SET, but never thought to frame it as a game of perception rather than strategy. It’s more like a tuning fork for awareness, especially the way you describe playing it in sync with your partner. That feeling—two people quietly attuning to a shared rhythm without over-verbalizing it—is its own kind of intimacy. Thanks for naming it so beautifully.

Thanks for introducing me to this wonderful brain tickler. SET reminds me a lot of trying (unsuccessfully) to learn mahjong. In that way I think SET feels like a pure distillation of the pattern matching mechanics of other classic set making games: poker, mahjong, rummy etc. Many of those games have simpler patterns but build complexity with additional mechanics. It makes me wonder whether there is an optimal comfortable complexity for set making which allows for additional mechanics or if it's all a matter of training and familiarity