In my forthcoming book I sketch out the argument that Poker, a game developed for, and by, degenerate gamblers, maybe saved the world. In the early 20th century, John von Neumann, bored by the childish puzzles of math and physics, turned his thoughts to the dynamics of Poker. The results revolutionized economics, biology, and a bunch of other fields. In particular, game theory, the field he invented, provided a framework for thinking through the strategic and diplomatic logic of nuclear weapons and international conflict, including mutual assured destruction, that famous mechanism of nuclear deterrence.

(But Frank, I hear you say, I’ve seen Dr. Strangelove, I’ve watched The Trap, von Neumann is the bad guy, game theory is a reductive delusion, it’s probably more accurate to say game theory almost destroyed the world than to say that it saved it. To which I respond - maybe. I’ll grant you that it’s complicated. But right now I’m looking out the window at a beautiful June day, the sun is shining, the birds are singing, flowers are blooming. We aren’t trying to scratch our way back to civilization from the ashen wreckage of a post-apocalyptic wasteland. So at least we can agree that, so far, game theory hasn’t failed to prevent nuclear armageddon.)

Today we may stand on the brink of another potentially world-ending disaster. Or we may not, you know, it’s hard to tell. But, for the sake of argument, let’s say we do. After all, if you don’t believe that AI represents an existential threat, then the overreaction itself becomes something of a crisis, evidence that we are struggling to wrap our heads around the meaning and purpose of this technology we are inventing.

I want to suggest that, once again, games can help us navigate this crisis. Not, this time, by suggesting a formal model for analyzing multi-agent decision-making, but by providing a way of thinking beyond the limits of formal models entirely.

The Basic Premise

This way of thinking starts with a basic premise which I cannot prove because it is too deeply embedded in my world view to be isolated and questioned. Nonetheless, I’m confident many of you will allow me to assume this premise because it is deeply embedded in your world view too. The premise is: art matters. Art isn’t just decoration on the edges of life, it isn’t just a superfluous activity on the margins of culture. In ways that are hard to precisely articulate and through causal networks that are hard to clearly define, it matters, it makes a difference, it contributes in significant ways to the process by which the vast, world-shaping forces of history do their thing.

Novels, songs, paintings, films, poems, plays, and games, they matter. Not by making arguments and supplying evidence, but by crafting new experiences, creating particular states of consciousness, constructing shared dreamworlds, new cognitive modes, new ways of knowing, of being in the world.

In particular, art matters when it comes to questions of meaning and purpose, questions of value and value drift, questions like - What makes life good? What do we really care about? What are the threads that bind us to each other, and to our ancestors and our descendants?

If we are going to successfully adapt to a world with AI in it, we will do so not only via white papers and podcast discussions, op-eds and conferences and seminars and laws and regulations and books and blog posts, but also via sit coms and pop songs and stand-up routines and comic books. And, especially, games.

Why Games?

Games have, not only a special opportunity, but a special responsibility, to help humanity navigate this transition. Long before computers existed, games were crafting intricate, rule-based systems with surprisingly complex behaviors, creating rituals of procedural logic in which we put on the mask of algorithmic thinking, acting out what it would feel like to be nothing but a giant calculation flowing through the circuits of Chess, Mancala, Backgammon, or Go.

By flickering torchlight we put on these game faces and invited the spirits of computation to inhabit us. What would it be like to be GPT if it was like anything at all? Ask someone who has played a million hands of Poker. Seriously, ask them. Say: dude, what were you thinking?

Well, I was… Well, to be honest, I don’t remember exactly. I would say it seemed like a good idea at the time, but even at the time it didn’t seem like that good an idea. You can play a thousand hands of Poker, or ten thousand hands, and get most of the good stuff - the insights into probabilistic thinking and expected value and recursive opponent modeling. What you are doing after that, for the hundreds of thousands of hands after that, is giving yourself over to the process of glacial erosion by which the weights of the connections between the neurons in your brain are shaped to more and more resemble the solution to a single, well-defined problem. I was, hand by hand by hand, trying to make fewer errors. I was descending a gradient. I was minimizing regret. I was evolving a new way of seeing, and being in, the world - my p-p-p-poker face.

There are some problems that our brains can occupy in this way, or vice versa. Problems where the search space is so vast and complicated you don’t just lose yourself in them, you can find yourself in there too. Inhabiting a problem like this isn’t an anonymous, mechanical grind. Just knowing which direction to go requires giant maps of heuristics, principles, theories and philosophical ideas. And these maps are so large that they, themselves, require guides to navigate. Guides so complex that… well, you get the idea.

That these problems are tiny makes no difference. The right problem can open up a pinhole through which all of the light bouncing off of all of the universe makes a picture on the back wall of our head. We call these problems games.

I won’t deny that something similar happens when we read novel after novel, when we flip through album after album, when we sit in the dark, absorbing frame after frame. But games have a special relationship to this brain-hacking vision of art as self-modifying code.

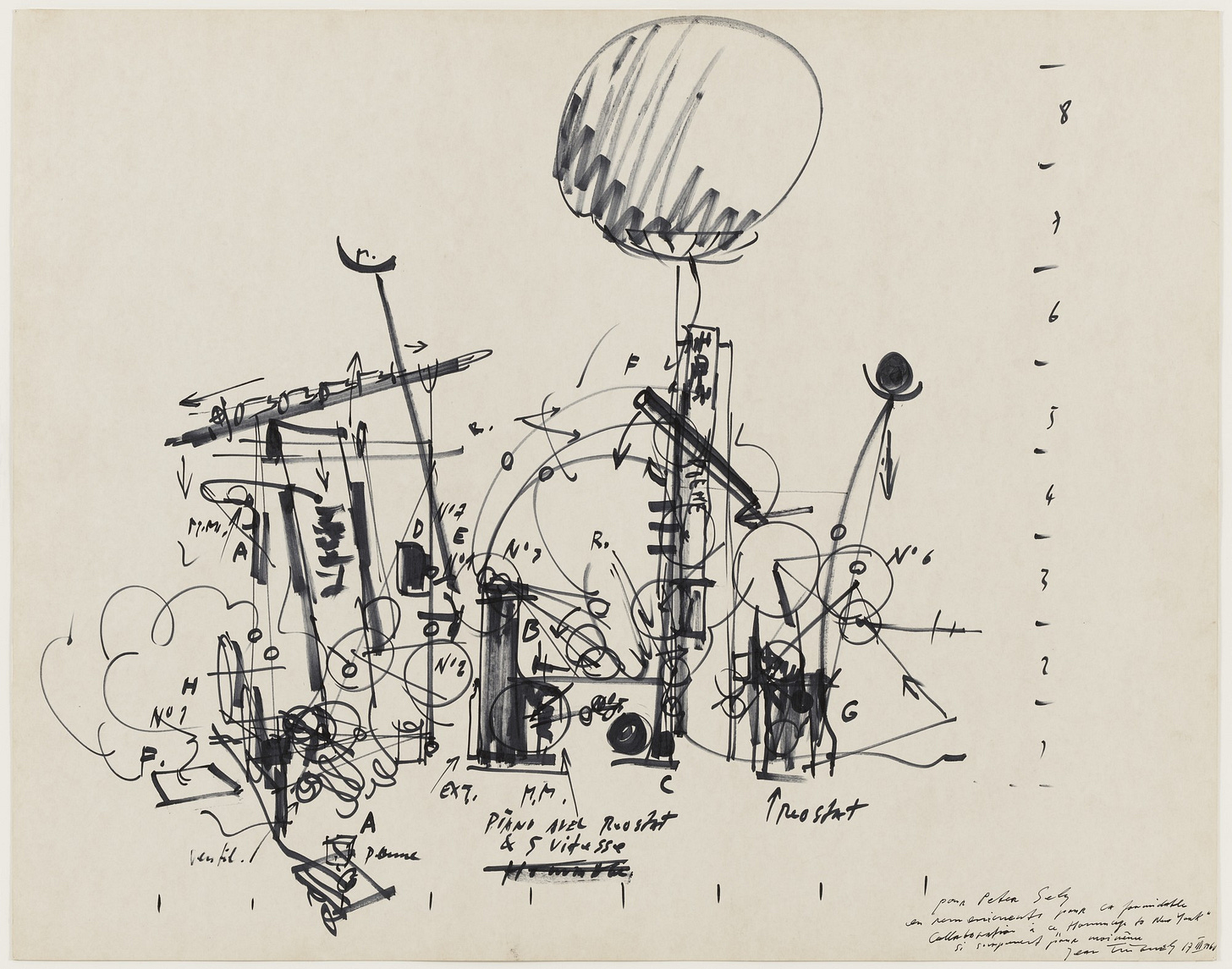

Long before Deep Blue existed, every Chess player knew what it was like to be a computer. And Duchamp knew that every Chess player was an artist.

(If you want a vivid picture of what life after bodies might feel like, I offer you this - the spirit of Marcel Duchamp, reaching out, through my brain, and my fingers, to be here now, to encounter this moment, to say yes! I see it! The chocolate grinder! The bachelors! The bride! He did. He did see it. But what force compels me to say it? Language lets me repeat the words he said, but it is something that precedes language, and will outlive it, that makes me type them.)

dude, what were you thinking?

Here’s another possible answer: thought is beautiful. In addition to being, whatever you would call it - useful? Necessary? It is also beautiful. Especially the kind of thought you experience when getting things done in the world, when actively engaged with a problem or situation, where you consciously and unconsciously bring to bear your abilities as an agent to influence the outcome, through skill, or luck, or strategy. It’s beautiful. Just look at it! Or maybe that’s just what thought is, this experience of getting things done, of being in the world, of being actively engaged with a situation, of bringing our abilities to bear in response to that situation. And look how sweet it is when, instead of doing it, you hold it up to the light, by pretending to do it in this particular way. Swish. Nothing but net.

Games are beacons, radio towers tuning in signals that travel in waves across the medium of pattern itself - across what it means for patterns to be stable, dynamic, persistent, responsive, creative, to exist. Computers bootstrapped themselves into the world by hitching a ride along this wavelength, a side-effect of the question “what can rules do?” asking itself.

For thousands of years, games have been the AI labs where humans did gain of function research on instrumental reason. What is it made of? How does it work? What are its limits? What does it feel like? Can I have some more? It is no coincidence that, once computers got here, and the project of AI acquired its official name and proper, scientific status, games became its primary testbed. Where better, than these miniature worlds made of ideas - rules and symbols - to discover the secret incantations that will… that will… what?

What were we doing, all of those thousands of years we spent hunched over a wooden matrix, uncoiling the incantations with our little monkey fingers? Well, one thing we were doing was getting off. It felt good. This is one of the ways that art matters. We did it for pleasure. We did it for beauty. We did it because it was cool. We did it looking for something else, something more than the daily grind. We did it for love.

But here’s the thing - it matters that, in games, when we painted our faces with numbers and gathered in circles to invite the spirits of thought and action to enter us, we invited them to take us over temporarily. Games are like pictures, and stories, and songs. They take us over temporarily, and we move between them.

We go into games and we come out of them. We think about them afterwards, and compare them to each other. And like pictures, stories, and songs, most of them are terrible. We know that. But some of them are beautiful. And sometimes we love the terrible ones for reasons we can’t quite explain. And we argue about which ones we like the most, and why. What does it mean for an optimization process to be interesting or boring? What does it mean for a simulation to be beautiful or cloying? What does it mean for a possibility space to be novel or cliched? What does it mean for a reward function to be deep and compelling or just hypnotically compulsive?

And that’s why. I think. That’s why games have, not just the power, but the special responsibility to help us figure this stuff out.

But How?

Oh, you want to know how games are going to save the world? Join the club! It is the nature of creativity to be impossible to predict. But here are five things that, for me, seem like clues.

KataGo vs Team KataGo. A few weeks ago, I wrote about a fundamental flaw discovered in state of the art Go AI. Ever since then, I’ve been thinking about how the KataGo team is responding to this issue. (I think it’s just one guy, David Wu, but in my head I imagine a whole dev team wearing NASCAR style eSports jackets.) I assume that they are figuring out how to fix this flaw, but what’s interesting to me is the nature of the overall loop. KataGo has the godlike power of playing Go at a level far beyond human capability, but it is incapable of recognizing when it is being punked by an adversarial strategy. It doesn’t know that it is losing a bunch of games in a row to an amateur player, because it has no awareness of anything beyond the current game. Team KataGo has the mundane, common-sense power of noticing the obvious fact that KataGo is shitting the bed and the ability to re-tune the engine to fix it. There’s nothing special about Team KataGo’s power. In fact, it’s easy to imagine automating it, adding a module to KataGo that tracks some simple metrics about its results, flags problems like this, and has some way to self-modify in response. The thing about this module is that it would, by necessity, operate by a logic completely orthogonal to the logic that structures the actual engine. The engine knows only Go, but the module knows something about the engine-in-the-world (which reminds me of Iain McGilchrist’s theory about the complementary role of the brain’s two hemispheres.) I picture this new overall system of engine + module as having a crude form of self-awareness, a kind of simple caring, even something a bit like emotions. I also imagine that, while more robust to certain kinds of adversarial attacks, it would become vulnerable to a new class of higher-level ones. And we just wanted something that could win at Go, a game with, like, three rules. What a wonderful mess!

Magnus Carlsen is bored. Magnus is the greatest Chess player of the contemporary era, maybe of all time. Recently, he doesn’t feel motivated to maintain this position, preferring to play Poker and speed Chess to classical, and, even in tournaments, playing sub-optimally on purpose as a goof. This is what actual general intelligence looks like. Yes, it is harder to keep Magnus safely on task, but it is is also harder to imagine him tiling the universe with mateonium.

The meta-morality of live Poker. Sometimes, when you play low-stakes Poker at a casino, you end up at a friendly table of casual players who, for the most part, are all playing according to a kind of tacit agreement - when you get the best hand you win. Occasionally they bluff, but mostly everyone is waiting to get lucky, which, over the long run, ensures that everyone gets an equal share (minus the rake), and we all get to enjoy the suspenseful roller coaster ride of fate together, while relaxing and having fun, sort of like if Poker was Bingo. Now picture a sweaty young try-hard dropping into this game, head full of Sklansky theory, trying to maximize his edge by punishing everyone for playing in passive and predictable ways. On the one hand, it’s a blast! On the other hand, it feels kind of gross. It’s easy to imagine one of the regulars thinking, “Sure, we could all do that, we could all work really hard, and make a big effort to play optimally, and then, eventually, when we were all playing perfectly, we’d be right back here, where, once again, the results are determined by fate. Only we’d be much worse off, because we will have all used up a bunch of resources just to maintain the status quo. Your precious Poker theory turns a perfectly fun zero sum game into a horrible red queen race.” To which the sweaty young try-hard responds, “For me, that is the fun.”

How to play Hanabi. Hanabi is one of the greatest games of all time. It’s a cooperative game that is especially fun as a two-player game where you play with same person over and over again, evolving shared instincts, heuristics, and skills. My wife and I played this way for years. At one point, we had a very interesting discussion. You see, in Hanabi you are trying to sort the cards into 5 piles of 5 cards each, and at the end of the game your score is how many cards you successfully sorted. Now, given these rules, there are two different ways you can play - you can play to maximize your expected score, or you can play to maximize your chance of getting a perfect score of 25 - and these different goals lead to slightly different strategies. The rules of the game, despite precisely articulating a specific goal, don’t answer this question for you. Instead, you have to consider the context, how the game fits into the world. For instance, if you were in a tournament where your team’s score across multiple rounds determined the results, you would want to maximize expected score. But there wasn’t any explicit context telling us how to play. Instead, we had to ask ourselves - why are we playing? What do we value about this game? And which context would give us more of that?

Bernie De Koven, from The Well-Played Game:

It is neither work nor play, purpose nor purposelessness that satisfies us. It is the dance between.

Games are the artform of systems, of software. Through them, we reach for something else, and this something else is what gives them leverage on the daily grind, lets us see it by being not it. But, at the same time, the daily grind gives us leverage on them.

There is no special feature of software that will, if arranged properly, carefully, just so, make us safe. To the degree that we are safe, it is because of the messy and complicated ways that software is embedded in the world. Just like there is no special feature of us that makes us human, just the messy and complicated ways we are embedded in the world.

Looking for a technical solution to the alignment problem is like looking for the off button inside of Chess. There is no off button in Chess, it’s out here, with us.

Some random threads of thought provoked by this essay:

My favourite definition of art and argument for its value comes from Susan Sontag's essay 'On Style'. In it she writes "Art is the objectifying of the will in a thing or performance, and the provoking or arousing of the will. From the point of view of the artist, it is the objectifying of a volition; from the point of view of the spectator, it is the creation of an imaginary décor for the will." And also "The overcoming or transcending of the world in art is also a way of encountering the world, and of training or educating the will to be in the world"

To the extent that cultivated will is one of humanity's most prized possessions, this is a way to understand why art matters.

The definition I think may also have interesting connections with the work of C. Thi Nguyen and his philosophy of games, in particular his book Games: Agency as Art (though I haven't read it yet):

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/327681947_Games_Agency_as_Art

The messy and complicated ways that software is embedded in the world are important. But the Mongols were embedded in the world in messy and complicated ways; that didn't prevent them from destroying large parts of it.